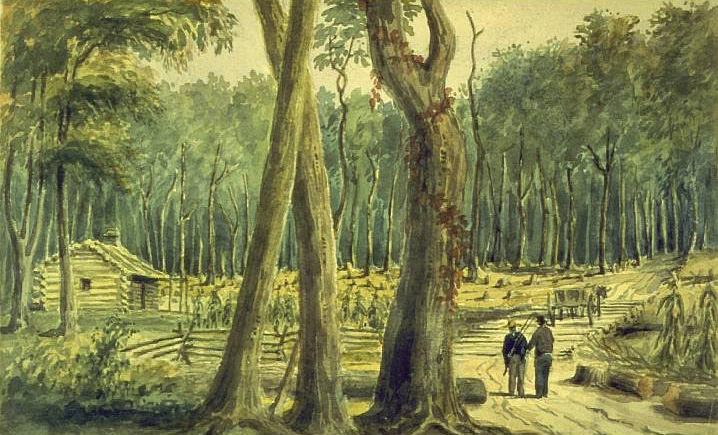

Moodie Farmsite 1

Gage’s Creek

The rain poured in at the open door, beat in at the shattered window, and dropped upon our heads from the holes in the roof. The wind blew keenly through a thousand apertures in the log walls; and nothing could exceed the uncomfortableness of our situation. For a long time the box which contained a hammer and nails was not to be found. At length Hannah discovered it, tied up with some bedding which she was opening out in order to dry. I fortunately spied the door lying among some old boards at the back of the house, and Moodie immediately commenced fitting it to its place. This, once accomplished, was a great addition to our comfort. We then nailed a piece of white cloth entirely over the broken window, which, without diminishing the light, kept out the rain. James constructed a ladder out of the old bits of boards, and Tom Wilson assisted him in stowing the luggage away in the loft.

But what has this picture of misery and discomfort to do with borrowing? Patience, my dear, good friends; I will tell you all about it by-and-by.

While we were all busily employed—even the poor baby, who was lying upon a pillow in the old cradle, trying the strength of her lungs, and not a little irritated that no one was at leisure to regard her laudable endeavours to make herself heard—the door was suddenly pushed open, and the apparition of a woman squeezed itself into the crowded room. I left off arranging the furniture of a bed, that had been just put up in a corner, to meet my unexpected, and at that moment, not very welcome guest. Her whole appearance was so extraordinary that I felt quite at a loss how to address her.

Imagine a girl of seventeen or eighteen years of age, with sharp, knowing-looking features, a forward, impudent carriage, and a pert, flippant voice, standing upon one of the trunks, and surveying all our proceedings in the most impertinent manner. The creature was dressed in a ragged, dirty purple stuff gown, cut very low in the neck, with an old red cotton handkerchief tied over her head; her uncombed, tangled locks falling over her thin, inquisitive face, in a state of perfect nature. Her legs and feet were bare, and, in her coarse, dirty red hands, she swung to and fro an empty glass decanter.

“What can she want?” I asked myself. “What a strange creature!”

And there she stood, staring at me in the most unceremonious manner, her keen black eyes glancing obliquely to every corner of the room, which she examined with critical exactness.

Before I could speak to her, she commenced the conversation by drawling through her nose, “Well, I guess you are fixing here.”

I thought she had come to offer her services; and I told her that I did not want a girl, for I had brought one out with me.

“How!” responded the creature, “I hope you don’t take me for a help. I’d have you to know that I’m as good a lady as yourself. No; I just stepped over to see what was going on. I seed the teams pass our’n about noon, and I says to father, ‘Them strangers are cum; I’ll go and look arter them.’ ‘Yes,’ says he, ‘do—and take the decanter along. May be they’ll want one to put their whiskey in.’ ‘I’m goin to,’ says I; so I cum across with it, an’ here it is. But, mind—don’t break it—’tis the only one we have to hum; and father says ’tis so mean to drink out of green glass.”

My surprise increased every minute. It seemed such an act of disinterested generosity thus to anticipate wants we had never thought of. I was regularly taken in.

“My good girl,” I began, “this is really very kind—but—”

“Now, don’t go to call me ‘gall’—and pass off your English airs on us. We are genuine Yankees, and think ourselves as good—yes, a great deal better than you.

– Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush (1852)